Dali: Religious Mysticism and the Hypercube

Corpus Hypercubus or Crucifixion, painted by Salvador Dali in 1954, is a merging of Dali’s late association with Catholicism, and his devotion to mysticism that come together in his signature surrealist vein. The painting blends the stark and traditional religious theme from the Renaissance with the more modern associations of art with psychology and geometry. Corpus Hypercubus has visual order that sustains the scene and makes it relevant in modern art.

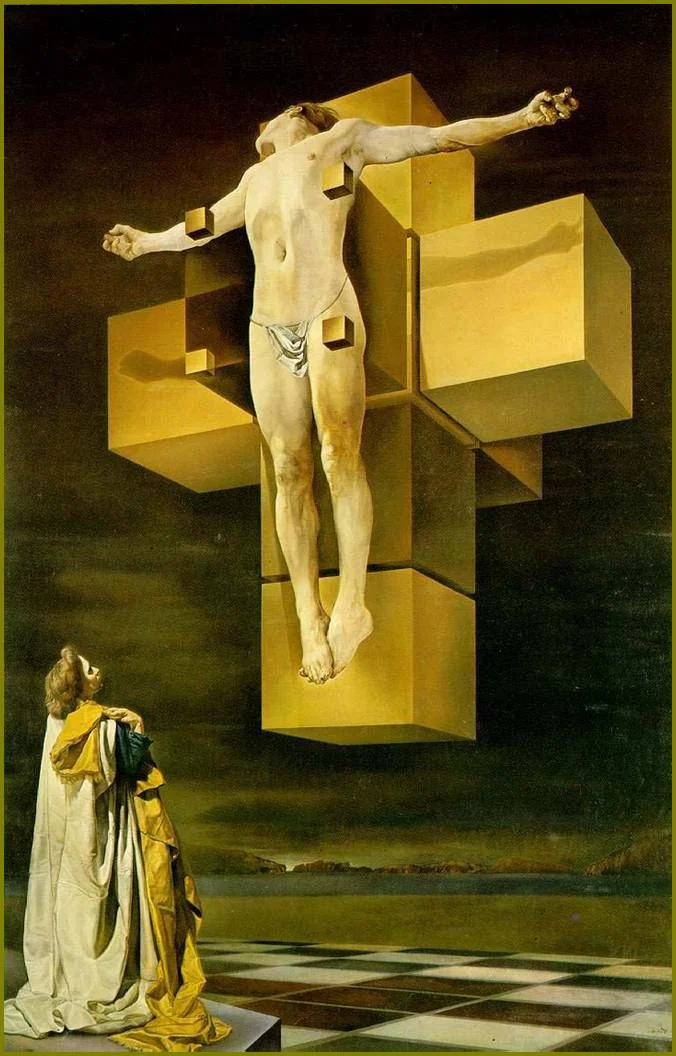

Corpus Hypercubus is an oil and canvas painting. The title concerns the main image of Christ on the cross: “corpus” meaning body and “hypercubus” in reference to the geometric shape of the cross. This is the image that the eye is first drawn to. The cross then leads the eye down to the figure of Mary, painted brightly in the corner, then to landscape in the background. Though it is very abstract, it is also painted in the very defined manner with sharp lines typical to Dali’s style. It is not necessarily a social commentary but rather the presentation of a new point of view of a scene that has been depicted many times over. It is seemingly intended for a wide patronage, as Dali did have a large fan base. [NERET, 80]

The elements of science and geometry that Dali uses in this work come through with his use of the hypercube as the cross. The hypercube is a type of hypergraphic, a type of shape that displays geometric and scientific conceptions of shapes and shares them with artistic visual forms. [BRISSON 258] Further more, they can even relate to philosophical beliefs and trains of thought which explains why Dali made such abstracted use of the hypercube in Corpus Hypercubus. But Dali uses an even more deconstructed form of the hypercube that breaks it down into eight connected cubes that form the shape of the cross Dali uses as the crucifix. [BRISSON 259] The tiled floor in the foreground mirrors the shape of the hypercube from below and the repetition of squares helps to stress the mix of geometric and organic forms in the painting. This type of integration of scientific ideals into religious phenomena is really what defines this work of art and others painted by Dali around the same period.

Corpus Hypercubus is set apart from traditional Renaissance portrayals of the Crucifixion through modern Surrealism and Dali’s expansion on the style. The dream-like depiction of Christ exhibits a large figure in comparison to Mary alluding to Christ’s significance. This is a technique used in Early Italian Renaissance art to emphasize the subject. A typical Renaissance style is also suggested through Mary’s draped robe. The technique of painting draped clothing was greatly improved upon during the Renaissance and Dali brings this form into his modern work, possibly paying homage to the many classic crucifixion scenes painted before his.

Corpus Hypercubus is a fine example of how Dali’s paintings came from his psyche. He painted his beliefs and illusions almost in pursuit of reflection and further understanding of his own mind. His work over the years plumbed the depths of Surrealism, taking cues from Freud’s psychoanalysis, the symbolism in mythology, and the spirituality of Spanish mysticism. [NERET, 79 2002] [WHITFEILD, 52, 1999]. With a career full of these mind-boggling and erotically charged works of art, Dali turned to more classic and religious themes as early as 1943. [KING, 26]. Corpus Hypercubus is a product of Dali’s conversion to Catholicism and passion for mysticism. He developed a blend of religion and science that he called “Nuclear Mysticism,” the category under which Corpus Hypercubus exists. [KING, 26]. Through his visual work, Dali strived to understand the miracles of his faith by trying to ground them in science. For example, he asserted that the Virgin’s assumption into heaven took place through a process involving antiprotons. [KING 30]. He wanted his faith to be grounded in reality, forever stuck between agnosticism and spirituality.

The composition of this painting captures the eye through the large and static depiction of Christ on the cross. He floats above a vast and desolate landscape as Mary mourns him from the lower left corner. The figure of Christ floats before the cross in a state of levitation. Dali depicted levitation in much of his religious art in reference to the ‘mystical ecstasy’ said to have been experienced by some saints. [KING, 27] Christ is a muscular figure and the usual stigmata and crown of thorns are absent. This is meant to capture the joy and beauty of the moment in religious history rather than emphasizing sorrow and pain as the scene is usually presented. [KING, 32] It is unusual that the viewer is not shown Christ’s face. Instead, his head is tilted away from the viewer showing only his chin. In fact, the face of Mary is not emphasized either and is shown from the side partially in shadow. Perhaps Dali wished to stress the supernatural aspects of the painting to make it more about the event than its two iconic figures.

Mary is shown dressed in a lavish gown and robes, standing on a raised platform in the corner above a tiled floor that meets abruptly with the landscape. She gazes longingly at Christ. Dali’s wife Gala posed for Mary in this portrait as she did for many figures in Dali’s paintings. [NERET, 80] There is a definite light source in the composition but there seems to be a second one that highlights Mary’s face, perhaps emanating from the figure of Christ.

The coloring in the sky leads the eye to the cliffs at the distant horizon, which seem to be concealing a light source, glimpsed through a break between the cliffs. The sky is dark and stormy, painted in dark grays and blues, evoking a feeling of something ominous and foreboding, appropriate for the subject matter. Dali uses yellows and golds to capture light in the foreground. The flesh tones all have a yellow tint as well as the cube-like cross, hinting at the divineness of the light that falls on the two figures and the scene. Yellow is also present in the sky, drawing attention away from the subject of the painting.

Dali emphasizes Corpus Hypercubus by using and expanding on his visual techniques. There are elements of modern forms as well as hints of a classic Renaissance style. The painting utilizes the stylistic and philosophical tools that Dali was known for and converts them into a work that is deeply reflective on his personal faith.

References

1. Harriet B. Visualization in Art and Science. Leonardo. 1992; 25(4): 257-262. In: Jstor [database on the Internet]. [Place unknown]: The MIT Press; [cited 2011 Apr 9]. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1575847

2. King E. Salvador Dali: The Late Work. London: Yale University Press.

3. Nadeau M. Dali and Paranoia-Criticism. In: The History of Surrealism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1965. p. 183-190.

4. Neret G. Salvador Dali. Germany: Taschen; 2002.

5. Whitfield S. Salvador Dali. Liverpool. The Burlington Magazine. 1999 Jan; 141(1150): 52-53. In: Jstor [database on the Internet]. New York: Pace University; [cited 2011 Apr 4]. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/888233